Enter the Sea Dragon

Revealing the secrets of a 230 million year old graveyard

Ichthyosaurs are a group of extinct dolphin-shaped marine reptiles that flourished in the oceans through much of the Mesozoic Era (250-66 million years ago). Although they lived during the age of dinosaurs, ichthyosaurs are not dinosaurs, but a distinct reptile group only distantly related to them.

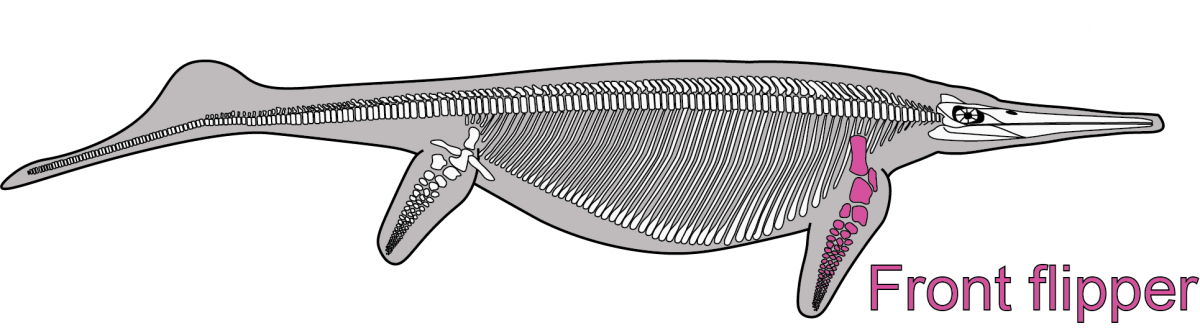

Their bodies were streamlined, with long snouts, flipper shaped limbs, and dolphin-like tail flukes. There were many different ichthyosaur species, some were the size of a salmon–roughly 3 feet or 1 meter in length–or but others grew as large as whales, more than 65 feet or 20 meters in length! Most hunted fish or other small prey, but some fed on other marine reptiles, much like killer whales that hunt other marine mammal species today.

Ichthyosaur fossils have been found on every continent but they are particularly well known from Europe, east Asia and North America. Some of the biggest and most intriguing ichthyosaur fossils come from the state of Nevada in the United States. One spot, near the former silver mining town of Berlin, is famous for its abundant giant ichthyosaur fossils.

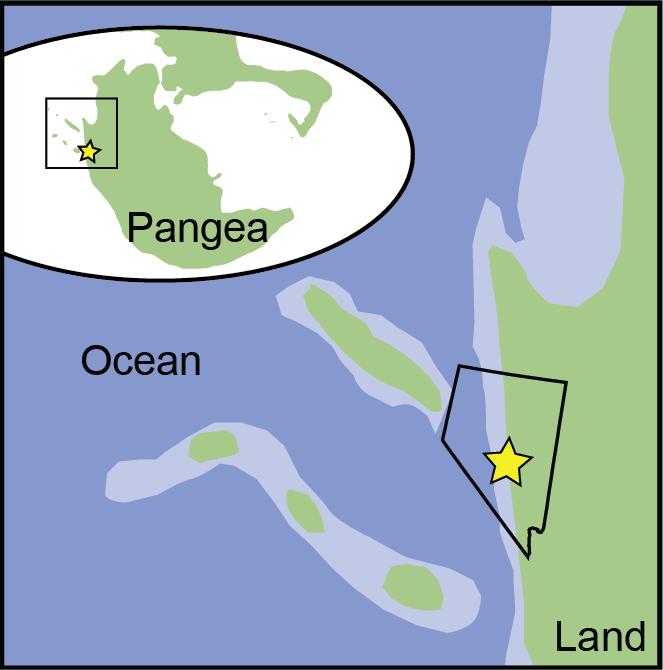

Although it is in the middle of the desert now, rocks and fossils show that much of Nevada was once underwater. For millions of years ichthyosaurs swam in the warm shallow seaway that covered this area. When they died, some were buried in mud at the bottom of the ocean floor. Later as the continents and oceans shifted and transformed, these skeletons were preserved as fossils and eventually revealed as the rocks containing them wore away.

North America Today

...and 230 Million Years Ago

This building in the remote desert of central Nevada holds a secret: piles of giant ichthyosaur bone exposed on a single rock layer.

Bones or rocks?

At first glance, the giant ichthyosaur bones look very much like the limestone rock that they are preserved within.

But with careful cleaning and study the bones reveal themselves. Here the bones have been color coded, each color represents a different skeleton.

These circular bones, roughly the width of a dinner plate, are individual bones, known as vertebrae, from the spinal column. With their long bodies and tails, ichthyosaurs had many more vertebrae than most land-living animals.

This flattened triangular shaped pile of bones includes the skull and jaws of one of the animals preserved in this quarry.

Although teeth are not well preserved in any of these skeletons, our new fossil discoveries from the same species reveal a row of sharp, pointed teeth suggesting Shonisaurus was a predator that probably fed on fish and other marine reptiles.

This is the upper arm bone. Although ichthyosaurs evolved from four-legged reptiles they adapted to life in the ocean by modifying their limbs into flippers.

This is the leg bone. Ichthyosaurs had flipper shaped hindlimbs as well as forelimbs.

The flippers of Shonisaurus were as long as a person!

These small bones are part of the tail. The tail of most ichthyosaurs was bent and supported a tail fin that helped push the animal forward through the water.

Skeleton Crew

Each color is inferred to represent parts of the same skeleton. Some skeletons broke apart on the seafloor. The absence of small bones suggests ocean currents pushed the skeletons around before burial and removed some of the smaller pieces.

The skeletons have partially fallen apart during decay and burial and none is complete. However we can determine that there were at least seven different skeletons preserved on this rock layer, probably more!

We can tell based on what is preserved that these animals were the length of a school bus (11-15 meters or 35-50 feet long).

What does it all mean?

While ichthyosaur fossils are very common in a few spots around the world, it is unusual to preserve so many individuals in such a small space and on a single layer of rock. It is possible that these animals lived together, like a pod of whales. Or, these might have been usually solitary animals that sometimes gathered at this spot in large numbers as some sharks do today.

Want to see more?

Image Credits: Gabriel Ugueto; Google Earth; Photo of UMNH VP 32539 courtesy of the Natural History Museum of Utah (UMNH) & U.S. Forest Service; NOAA - public domain; Photo of NVSMLV VM-2014-057-FS-001 courtesy of the Nevada State Museum, Las Vegas; Ryan Espanto - CC BY 2.0

3D data captured by the Smithsonian's Digitization Program Office in partnership with the Department of Paleobiology at the National Museum of Natural History.

We thank the U.S. Forest Service & Nevada State Parks for permission to conduct research.