As we explore our world, scientists must distinguish known organisms from each other and document newly identified species. The study of taxonomy uses multiple lines of evidence to determine if a particular species is related to another via common descent. To understand and systematically organize the diversity of life on Earth, researchers analyze specimen collections (like this one at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History), morphology, genetics, and any available information about the organism’s traits and life cycle.

The naming process of scientifically species often includes creativity and descriptive language based on Greek and Latin.

Acropora cervicornis

The Origin of Names

While a plant or animal will have different names according to local language and culture, standardized scientific naming follows the Linnaean Classification system. Carl Linnaeus developed the first modern system of binomial nomenclature (meaning the use of two names). When we refer to a organism by its scientific name, the genus is referenced first, followed by the species. In writing, a scientific name is italicized, with the genus capitalized and species in lower-case.

Today, naming a species must follow the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, which incorporates the organism’s evolutionary history.

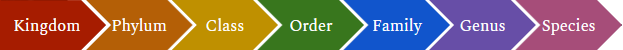

Order of Linnaean Taxonomy:

Agaricia speciosa

A ‘holotype’ specimen is the original, physical example of which a species is first formally described. James Dana collected this branching coral from a reef in Fiji over 150 years ago and named it Manopora digitata, designating this specific specimen as the holotype for M. digitata. Today, scientists refer to this specimen when identifying other individuals of this species (now synonymized as Montipora digitata).

The name of this species digitata comes from the latin root ‘digitus’ meaning ‘finger’ or ‘toe.’ Based on this, can you guess a common name of this coral?

Manopora digitata

This specimen is a ‘syntype,’ meaning it is one of two or more specimens used to originally name and describe its species. Species with syntypes do not have holotypes.

The genus name Acropora means ‘top opening’ and describes the axial corallite that sits on the tip of the branch (corallites located further down and around the branches are called radial corallites). In contrast, the species name humilis means “low” or “shallow.” This could be a reference to the shallow habitat this coral occupies - colonies are often exposed to the air at low tide.

Can you think of any other words that start with “acro” or “humil”?

Madrepora humilis

The way we name and classify organisms isn’t perfect. When we don’t have enough information to conclusively determine where a specimen falls along the framework of modern taxonomy, the specimen is labeled as ‘taxon inquirendum.’

Gemmipora brassica

Many species names you’ll discover in this digital collection have been synonymized, meaning taxonomists have updated classification based on new information. Though name changes can be frequent and confusing, they help us better understand the evolutionary history and ecosystem functions of the species we observe.

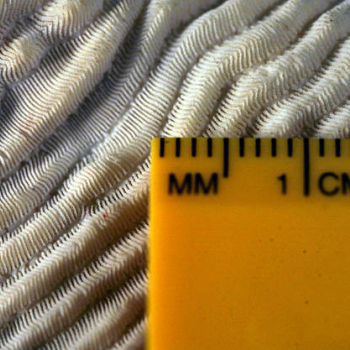

This is a macro (close-up) scan of Manopora lichen. You can view a model of the whole colony at the end of this section.

Manopora lichen

Collecting Corals

Many of these specimens were collected by Dr. James Dwight Dana on the United States Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842. Dr. Dana was an American explorer, volcanologist, and mineralogist who, during this expedition, described volcanoes and coral reefs throughout the Indo-Pacific, including in Singapore, the Philippines, Kiribati, Samoa, Fiji, Tahiti and Hawaii.

Seriatopora hystrix

Natural history collections are indispensable resources for cataloging the diversity of life on Earth. Many institutions do more than display specimens - they exist as research facilities that continue to explore and understand the natural world.

Distichopora violacea

Species of the genus Stylaster are known as ‘lace corals’ and belong to the class Hydrozoa. Hydrozoans belong to the phylum Cnidaria, along with jellyfish, anemones, and reef-building corals.

Stylaster sanguineus Valenciennes

Many specimens like this one were collected during the U.S. Exploring Expedition, have been stored in the Smithsonian for over 150 years as dry samples (in contrast to wet preservation in jars). They have been catalogued, photographed, and kept safely in drawers or on shelves at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C. This way, they are available for current and future scientists to study.

Specimens like these narrate stories of biological diversity over the course of Earth’s history. This unique perspective allows researchers to study patterns over time and better understand modern day issues like habitat loss, invasive species, and climate change.

Madrepora valida

Museum collections can have complicated origins, as many items procured over centuries are clouded by ecological damage and violence. For instance, during the U.S. Exploring Expedition (1838-1842) when many of these specimens were collected, expedition members initiated violent conflicts with Pacific Islanders.

In acknowledgement of historical transgressions tied to their collections, museums are increasingly committing to the repatriation of cultural artifacts, whereby objects are returned to their native origins and owners. With the development and adoption of reality capture methods like photogrammetry, 3D models of repatriated items can remain part of museums’ digital collections. In this case, these physical specimens remain at the Smithsonian Institution and the digital coral reef collection is now open access for anyone to view and study.

Pavonia decussata

With the emergence of photogrammetry- a method for creating digital 3d models by taking a set of photographs of an object from different angles to be “stitched” together- these coral specimens are available for anyone to explore on their computer screens. Digital replication and distribution make these objects widely available for study and discussion, without needing to visit the Smithsonian or risk damage or loss through museum exchange.

Manopora scabricula

The Smithsonian museum collection is made up of over 150 million specimens, artifacts, and artworks. Due to physical space limitations, varying levels of relevance to current exhibits, and physical fragility of items, only about 1% is on public display at any given time. Museums therefore are recognizing the value in digitizing their collections for widespread access via the internet.

This is a scan of a colony of Manopora lichen. You can view a macro (close-up) model of the corallites in slide earlier in this section.